|

|

[Bed linens made of Goose Down or Feather]

[Goose Feather and Down]

[Feather and Down production]

[Down Comforters and Down Duvet Covers] Goose Feather and Down

One service provided by feathers is that they help birds control their body temperatures. Fluffed-out feathers trap air, and hardly anything insulates against cold weather better than trapped air. If you want a super-lightweight sleeping bag for extremely cold temperatures, it's hard to beat a bag filled with goose down, and down is the third kind of feather.

There's another kind of feather called a filoplume (FILL-oh-ploom), which is bristlelike or hairlike. Filoplumes often occur sparsely on the undersides of birds or on their wings, beneath their contour feathers. Basically they are like regular feathers without the vanes -- they are merely slender shafts and probably help keep the other feathers in their place.

How many feathers does a bird have? It depends on which bird we're talking about. Most songbirds possess 2,000 to 4,000 feathers, of which 30 to 40 percent are located on the head and neck. The next time you see a sparrow or pigeon, just imagine that in the small area of the head and neck there are probably over 1,000 feathers! This concentration of feathers around the head and neck reflects the need to protect the brain, more than anything, against temperature extremes. Most naturalists can tell stories about snakes and lizards caught outside during cold snaps, who were so dazed they didn't try to escape. As a general rule, the colder the climate a bird species lives in, the greater its number of feathers. A Tundra Swan was found to have about 25,000 feathers, of which some 80 percent were on the head and neck! If you watch birds at times other than when they're feeding, you'll be amazed at the amount of time they spend preening -- caring for their feathers. If you spot a flock of House Sparrows enjoying their mid-day roost, notice how frequently individuals launch into frenzies of scratching, feather-combing with the bill, and other feather-care exercises. Preening birds often appear to nibble on something at the bases of their tails. When birds do this, they're gathering a special oil from their "preen gland." This oil is rich in waxes, fatty acids, fat, and water, and birds spread it over their feathers. Not only does the oil clean feathers, it also keeps them moist and flexible, improves their insulation capacities, and waterproofs them. Ducks usually have huge preen glands, for if a duck's feathers were not waterproofed with oil, they'd quickly become waterlogged, and the ducks would sink. Preen oil even helps control germs and lice on a bird's skin and feathers. The only way damaged feathers can be dealt with is to replace them entirely. If a feather is accidentally lost, a new one may quickly grow in its place. |

|

Privacy About Us Contact Returns Comments Affiliate Area Copyrightę A

Beautiful Bedroom, Inc. Site made by Tal Bahir. |

When

you think "birds," you can't avoid thinking "feathers." This is a good

mental linkage to make because feathers are one of the features making a

bird a bird and not, say, just a fancy lizard (which it almost is!) If

you've seen a plucked chicken, you know that only a small fraction of its

wing is flesh and bone, the rest being feathers. A featherless bird flapping

its wings is not much different from a lizard flapping its fore-arms.

When

you think "birds," you can't avoid thinking "feathers." This is a good

mental linkage to make because feathers are one of the features making a

bird a bird and not, say, just a fancy lizard (which it almost is!) If

you've seen a plucked chicken, you know that only a small fraction of its

wing is flesh and bone, the rest being feathers. A featherless bird flapping

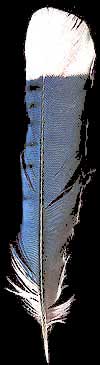

its wings is not much different from a lizard flapping its fore-arms. The picture at the left shows a feather-type known as a semiplume.

Semiplumes have shafts like contour feathers, but their vanes are fluffy,

not well organized with the barbs "zipped together" as in the contour type.

The picture at the left shows a feather-type known as a semiplume.

Semiplumes have shafts like contour feathers, but their vanes are fluffy,

not well organized with the barbs "zipped together" as in the contour type.

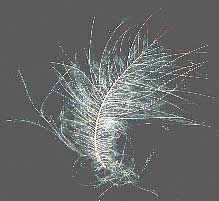

Down

feathers look just like semiplumes, except that their fluffy barbs all arise

from one point atop the "foot" of the feather (known as a calamus). In other

words, there is no shaft extending the length of a down vane. Down feathers

cover most newly hatched birds but on mature birds down is usually hidden

below the contour feathers. At the right you see a Bald Eagle nestling

covered with fluffy down feathers.

Down

feathers look just like semiplumes, except that their fluffy barbs all arise

from one point atop the "foot" of the feather (known as a calamus). In other

words, there is no shaft extending the length of a down vane. Down feathers

cover most newly hatched birds but on mature birds down is usually hidden

below the contour feathers. At the right you see a Bald Eagle nestling

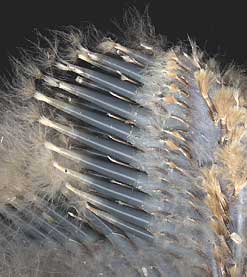

covered with fluffy down feathers. The amazing picture at the left shows the magnified wingtip of a very young

bird about to lose the down feathers it was born with. But to understand

exactly what you are seeing you must know a bit about how feathers grow. A

contour feather begins as a tiny pimple-like structure that eventually

produces the stiff, gray, plastic-looking, cylindrical items in the picture.

These are called feather follicles. Inside each follicle is an undeveloped

contour feather. Atop each follicle you can see individual down feathers,

which later will wear away and disappear as the contour feathers below them

emerge from the follicles. In other words, as the young bird develops, down

feathers are pushed from the feather follicles by the tips of the succeeding

feathers, to which they remain attached until they rub off.

The amazing picture at the left shows the magnified wingtip of a very young

bird about to lose the down feathers it was born with. But to understand

exactly what you are seeing you must know a bit about how feathers grow. A

contour feather begins as a tiny pimple-like structure that eventually

produces the stiff, gray, plastic-looking, cylindrical items in the picture.

These are called feather follicles. Inside each follicle is an undeveloped

contour feather. Atop each follicle you can see individual down feathers,

which later will wear away and disappear as the contour feathers below them

emerge from the follicles. In other words, as the young bird develops, down

feathers are pushed from the feather follicles by the tips of the succeeding

feathers, to which they remain attached until they rub off. Here

you see the underside of a wing of a Pine Warbler, Dendroica pinus. Notice

how the different kinds of feathers appear in different places, and see how

the large primary wing feathers overlap when the wing is open, forming a

kind of fan that can push against the air.

Here

you see the underside of a wing of a Pine Warbler, Dendroica pinus. Notice

how the different kinds of feathers appear in different places, and see how

the large primary wing feathers overlap when the wing is open, forming a

kind of fan that can push against the air.